Today we went for a trip into the bush with Marty. We were keeping her company while she looked for holes in the cattle fence lining the Maun-Francistown road. This is one of those things that was put up by Central govern,ment with the best intentions but does not really work in practice.

Here’s the reasons why. The fence is sparsely gated and a gate only works when it is closed. Most of the gate-posts we passed were ungated as gates are very useful to people elsewhere. Those gates we did see were either left open or mangled beyond repair. Long stretches of the fence were non existent for one reason or another. In many places the fence had been trampled down by either people or animals and ceased to serve it’s purpose.

Why is this such a problem? The fence is there to stop cattle and other livestock getting onto the road and being squashed. When there’s no fence the cattle get out and graze along the sides of the road as there is very good grasss there. So Marty’s involved with getting the fence repaired etc. We drove out of Maun at half eight this morning and traveled along the road playing a sort of Eye-Spy car game for sections of fence which was non existent, bent and climbable, gated and closed, gated but with no gate, gated with an open gate and gated with a mangled gate. We did pretty well.

This journey brought us to the turning for Samedupi so we went down there to see whether any water had reached the bridge. We were travelling through fully rural Africa . We’d left the builders merchants, car spares shops, garages, take-away’s and liquor rests way behind us on the outskirts of Maun.

The way was lined with species of acacia, sage brush, mophane and mogotho trees. Every now and then we’d see compounds with one or two ntlo or rondavel houses, a big tree for shade and people going about their business. We’d pass donkey carts laden with containers for water and usually a couple of boys or an old man at the controls.

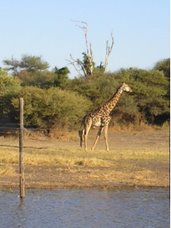

At Samedupi we got the first happy surprise of the day. Water had begun to flow in the Boteti river, a thing not seen for at least 20 years. It has been left in standing pools near Makalamabedi higher up the river in years prdeviously but had never flowed as far as Samedupi in about 20 years.

At the bridge it was coursing along like a mill-race and Marty pointed out that it was deep because the silcrete outcrops were submerged! Silcrete appears to be a little understoodmineral which forms somehow along rivers. It appears in stratified or nodular outcrops depending on how it was formed and can look like tree branches, trunks or rootrs which have become fossilised. The bits I saw reminded me a lot of the type of flint nodes which we found on Har Karkom when I was working with Professor Emanuel Anati’s yearly expedition there to catalogue the rock art. After all the Negev had once been a sea, and then had lakes and rivers. Thinking along those lines I asked Marty if she’d ever come across anything like the bulbusim you can find in the Negev and she had but much smaller and had at first mistaken hem for bolas stones.

We met a couple of local men on the bridge who were delighted with it and who pointed out fish to us. You could see on either bank people filling water and nearby work was going on on a pipeline. Marty found an acheulean hand axe on the bank, highly patinated. What marks these hand axes out is that they are shaped and pressure flaked before they are struck from the core.

We then continued on to Makamalabedi. Makamalabedi is a really pretty village. All the compounds are very neat and tidy looking and there are often well tended plants in them. Many of the traditional ntlo houses were decorated and had the traditional lowapa, a low wall creating a smaller space in front of the door. The veterinary fence that we passed through on our way to Meno A Kwena extends through here also and we had to pass the checkpoint. The friendly policeman there told us where we could get down to the river and so we went through the village and down there.

On our way we met a family in their Sunday best on their way to church and asked them when the river had arrived and it was only last night. We could see on the banks many people enjoying themselves. Children were splashing around as women and girls came and went with water containers. And everyone was very happy and you can understand why if you live in a desert next to a river which possibly hasn’t flowed in your lifetime.

We decided we’d carry on and see if we could find the leading edge of the river creping forward across the dusty earth. We went off the tarmac road and hugged the river banks. Along here were great molapo fields reacing almost from he crest of the bank down into the middle of the river beds. These are fields marked out by fences made from piles of acacia branches and saplings. They are quite an ingenious sort of agiculture. The idea is that you build your field and wait for he river to rise. Once the river has risen intoyour field you’re OK. Then as the water retreats you plant your crops and they are rooted well as trheir roots follow the retreating river water.

Down in the river beds we could see smaller area’s fenced off like this which were wells people had dug to reach the ground water. We had lunch in the shade of a tree high and dry up on the bank. Afterwards I went to look for scorpions in amongst the silcrete rocks on the river bed and scout a possible route back to the leading edge of the river through the field of spiky silcrete. What I found was the pelvic bones of a cow still joined at the symphysis and making a great mask for a sangoma. I took it back to where we were all sitting and Marty claimed it in the name of her grand-children.

I forgot to mention that on our way we’d lost sight of the river and when we came back to it it was dry as it ever was. Marty who can read landscapes like you can read the letters of this blog explained why. We could see that the river curved back to where we had last seen it and this curve was caused by the river having to edge round a large formation of silcrete below the topsoil.

OK, you’re up to speed now. So after lunch we continued back along the riverbank towards Makalamabedi weaving down to the river bed, up the bank and from one side of the riverbed to the other and passing molapo fields and wells along the way. Makalamabedi came back into sight above the river on the far bank then we emerged from the bush and saw a backie parked and a cluster of people so we headed towards them. The backie turned out to belong to Water Affairs and we’d found the leading edge of the river being very dramatic.

The river had found itself a nice narrow channel to creep along around the edge of the silcrete deposit. It had just arrived at the lip of a well dug in the river bed and the men from water affairs had broken the lip to allow the water into the well and replenish the groundwater. The water poured over the edge in a healthy torrent and to the delightof us and the onlookers swiftly filled the well and spilled over the edge and began to flow forward through the parched grass like so many glistening snakes.

So, how is it that a river which has been dry for 20 years suddenly return to life? The reason is good rains in Angola . One of the men from water Affairs told us that the waters were continuing to rise in the panhandle, i.e. the point of entry iof water to the Okavango Delta in northwestern Botswana.The river was a beautiful thing to see flowing through the desert, reflecting the blue of the sky and glittering invitingly through the trees. Just looking at it you can feel its coolness and really appreciate its importance, here in the desert as a source of life. This was something which I had never seen before, a river in the desert returning to life and I was sharing this amazement with the people who lived here some of whom had never seen the Boteti river flow in their lives. I may not see such a thing ever again in my life.

Friday, August 17, 2007

Exploring With Marty: The Return Of The River

Labels: Homoeopathy in the NHS Early Day Motion

Achulean Hand Axe,

Africa,

Boteti River,

Botswana,

Makalamabedi,

Samedupi

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment